Episode Description

You’ve seen one flutter by, regally flapping its iconic orange-and-black butterfly wings as it flies through your garden, over your balcony or past your window.

But did you know that once these little monarchs leave your yard, they begin one of the world’s longest migrations?

In this multinational episode, we join their multi-generational journey from Canada to Mexico, uncovering the astonishing science that keeps them going, the accelerating challenges they face along the route, and the host plant whose disappearance could ground them for good.

“They somehow take us back to our childhood. They're so beautiful. They are harmless. They're colourful. And I guess that every one of us, when we were a child, we saw a butterfly, or maybe even held one, and got fascinated by it.” –Jorge Rickards, director general, WWF-Mexico

Episode Transcript

ZIYA TONG: In Michoacán, a mountainous region west of Mexico City, there is a forest unlike any other. The trees are oyamel firs—tall, pointed evergreens that only grow on top of mountains, where the cloud cover provides the moisture they need to stay green. But if you visited this forest between November and March, you would never know the trees were green. Because all winter, the oyamel firs are covered from trunk to tip in monarch butterflies. Today is an important day for the monarchs. Something in the air has shifted. Maybe it’s the angle of the sun, or the temperature of the wind. Whatever it is, the dormant butterflies are starting to wake up. At first, it’s just a few of them. But what starts as a trickle slowly but surely becomes a flood. Millions of fluttering orange-and-black wings fill the air, climbing higher and higher. It’s an instinct. Somewhere in their tiny bodies, something ancient is telling them: it’s time to go north.

ZIYA TONG: I’m Ziya Tong, a science broadcaster and explorer of our beautiful planet. I’ve spent my career bringing nature to people and people to nature. On this podcast, we’re meeting the incredible species that call Canada home—and the people working to protect them. From WWF-Canada, you’re listening to This Is Wild.

ZIYA TONG: Monarch butterflies are found all over the world. But the monarchs in Michoacán are special.

JORGE RICKARDS: I remember my first trip to the monarchs was back in the 70s. My family and myself made this trip to this really remote place in Michoacán, it was very remote then, almost no roads to get to the sanctuaries, and I just could not believe my eyes when I saw that amazing amount of butterflies.

ZIYA TONG: This is Jorge Rickards. He’s the director general of WWF-Mexico. He’s been fascinated with butterflies since he was a little kid.

JORGE RICKARDS: My great-grandfather built a butterfly collection in the late 19th century, early 20th century, that I inherited. And I loved that collection when I was a kid. So I fell in love with butterflies and eventually was fascinated with the monarch phenomenon.

ZIYA TONG: The Michoacán monarchs really are a phenomenon—they’re some of the only monarchs on Earth that migrate. But this isn’t just any migration. Here’s how it goes: In late March, the monarchs begin to stir in the forest in Mexico. Slowly, one by one, they leave the trees that have been their home for the last few months, and head north.

JORGE RICKARDS: Once they reach northern Mexico, southern US, around Texas, all the border states, they lay their eggs there and a first generation there is born. So, you know, the life cycle of the butterfly, chrysalis, pupa, and butterfly, and then they fly up north again to another location in the midwest of the United States, and then eventually to southern Canada.

ZIYA TONG: Over the next few months, this happens 4 or 5 times. Each generation lives for around a month, passing the baton to the next as they make their way as far north as the Canadian prairies. That’s almost 5000 kilometres! But then, after a few months up north, something amazing happens.

JORGE RICKARDS: So they have to, not consciously, but biologically, make a choice. Now, I can try to endure the super low temperatures of lower Canada, northern US, or I can try to find a place that is warmer like my former generations did.

ZIYA TONG: These butterflies have a superpower, and it’s called the “reproductive diapause”. Basically, they need as much energy as possible to get back down to Mexico, so they just…shut everything down. They slow down their metabolisms and pause the growth of their reproductive organs.

JORGE RICKARDS: So because temperature begins to go down, the diapause triggers, and that means I'm gonna save my energy. I'm gonna use those lipids for my trip. So when you monitor the butterflies along the trip, we do that as soon as they cross the northern Mexico border, we begin observing them. We catch a few, we weight them, and we can see that they are fatter. Once they are getting down to Mexico, to Michoacán, the state where the overwintering sites are, they are very thin.

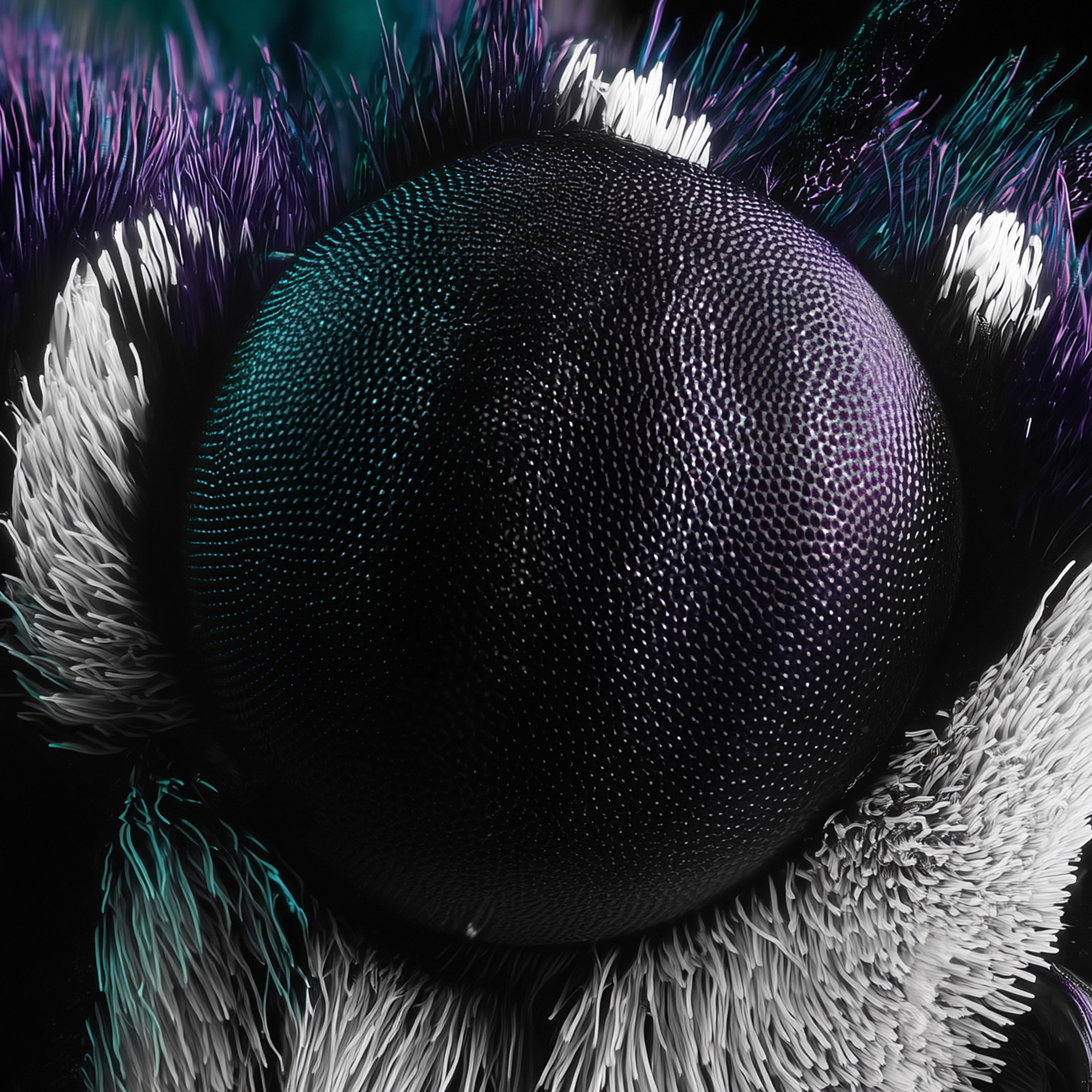

ZIYA TONG: Scientists call this a “supergeneration” and they can live for as long as 8 months. That’s like if, every fifth generation, human beings lived for over 500 years! Each new generation of monarchs is born with a kind of genetic memory. The supergeneration, the ones born in Canada, have never been to Mexico before, but something in their tiny minds tells them which way to fly. The world the monarchs live in is beautiful and vibrant. They have compound eyes, which allow them to see a kind of mosaic-like view, with a colour spectrum far beyond what you or I can see. To them, autumn wildflowers like aster and goldenrod look like neon landing pads, ready to fuel them on their long journey south. And they need those landing pads—because that long journey south gets tougher every year.

JORGE RICKARDS: So, butterflies, as any other species that are, have adapted themselves to certain patterns of nature, certain temperatures, wind occurrence, are now facing variability, a very marked variability in climate. That means more storms, more frequent, more severe, lower temperatures along the migration route, or higher temperatures along the migration route. So as a species, it will have to adapt, as any other species, to those changes.

ZIYA TONG: One of the major impacts of climate change is an increase in extreme weather.

JORGE RICKARDS: The risk is that, as fragile as it is, one storm can have an enormous effect on the entire population.

ZIYA TONG: That’s why the monarchs need to make it to Mexico—as strong as they are, they’re safer in their natural environment, where the forest canopy can protect them.

JORGE RICKARDS: That's the reason they concentrate on the fir. Once they are concentrated, they keep temperature more stable, they are less vulnerable to winds, a single butterfly is going to be flown away, but a clutch, a concentrated close clutch of butterflies is going to build a very compact unit. So that's what protects them.

ZIYA TONG: The oyamel forest in Mexico is the perfect place for the monarchs. It’s usually nice and warm, and the shape of the trees is perfect for protecting them from wind and rain. So, you might be wondering…why fly north at all? Well, it’s all about milkweed.

RYAN GODFREY: So monarch butterflies pick milkweed plants to lay their eggs on, because they have evolved this super special relationship. And this relationship goes way, way, way back. It's not unique to monarchs. So there's a whole group of butterflies that we only find in the tropics called the milkweed butterflies.

ZIYA TONG: This is Ryan Godfrey. He’s WWF-Canada’s resident botanist, and he knows all about how unique the relationship is between butterflies and their favourite plants.

RYAN GODFREY: It's almost like they all got together. and said, okay, I'm taking milkweeds, I'm taking willows, I'm taking asters, and they all just sort of divided it up. [laughs] That is not how it actually happened in nature. The evolutionary process is different. But essentially, yes, every butterfly has a special relationship with a type of native plant, and every native plant supports one or more types of butterflies.

ZIYA TONG: For monarchs, that native plant is milkweed, which gets its name from a milky white latex the plants produce. Milkweed is where monarchs lay all of their eggs, and it’s where their caterpillars hang out until they’re ready to become a chrysalis and start their life as a butterfly—which means that monarchs eat a lot of milkweed, too. But here’s the thing: milkweed is actually poisonous.

RYAN GODFREY: Most plants have defense mechanisms because they stay put. So they're a little bit vulnerable to creatures that want to eat them. And so what plants do is they invent chemicals. They are wonderful chemists, and that's how they protect themselves by basically filling their tissues with saps or other chemicals. And the milkweeds do that both with the latex. and then with this other type of chemical, which are called cardenolides.

ZIYA TONG: Cardenolides are toxic chemicals that affect the heart. So if an animal eats too many cardenolides, its heart might stop. But monarchs have figured out a nifty way to deal with that problem:

RYAN GODFREY: So the milkweeds are trying to protect themselves. That basically prevents any insect from being able to eat them without dying. But monarchs, some time ago, they evolved a way to take that toxin, the cardenolide, and bring it into their body, into their tissues. So they become poisonous, in the same way that a milkweed is poisonous. And then when something tries to eat them, they mess with the heart of that bird or other creature. So imagine that you wanted to, I don't know, turn your hair green and you just can eat a salad and then take the green from the salad and put it into your hair. That's basically what the monarchs are doing. They're taking their food and processing it and bringing it into their body and becoming, in a way, part of that plant, which is wild, frankly.

ZIYA TONG: So milkweed is essential for the survival of the monarchs. They fly north because that’s where they have the best chance of finding this very special plant.

RYAN GODFREY: So when they're up here in northern United States and southern Canada, monarchs are looking for milkweed and laying eggs and hatching from their eggs and then eating the leaves of milkweeds. Oftentimes, you can find females looking at and tasting different plants. They taste with their feet, and they're tasting for, hmm, is this a place where I can lay eggs? And, you know, flapping around, trying not to get eaten, or crawling around if they're in their larval stage, just munching, munching, munching.

ZIYA TONG: But the problem with relying on a poisonous plant for survival is that humans aren’t very interested in keeping your favourite food around.

RYAN GODFREY: So farmers, particularly cattle farmers, identified it as a noxious weed. Why is it a noxious weed? Because it has a chemical in it that messes with the hearts of any creature that has a heart, and guess what? Cows have a heart, cows eat milkweed. and then they get sick and sometimes die.

ZIYA TONG: Farmers often spray their land with herbicides designed to kill any and all plants that aren’t crops or food for animals. And that means a lot less land for milkweed.

RYAN GODFREY: So it's very intentional, like it's very much humans decided we don't like this plant and we want to get rid of it. And unfortunately for the monarchs, that really messes with their entire life cycle, their whole deal. The whole reason that they came up here was for the milkweeds, presumably, and here we are removing it from the landscape.

ZIYA TONG: It’s not easy to count butterflies, as you might imagine, so scientists check their population by measuring how much land they take up. In 1997, monarchs covered about 18 hectares of the forest in Michoacán. In 2024, WWF found that the Michoacán butterflies were covering less than a hectare. That’s a 95% drop in population in less than thirty years. For a long time, one of the drivers of that decline was logging and farming activity in the butterflies’ overwintering site. According to Jorge Rickards from WWF-Mexico, the only way to tackle that problem was to work directly with locals.

JORGE RICKARDS: So Mexico is a country that, after our revolution, was very much an agrarian revolution, the government gave the land to the people. So plots of land were given to groups of people, to communities. And nowadays, that is the way most of Mexico is divided. Most of these communities had legal permits to extract wood from their forests. So when the reserve was established, their permits were canceled. And so the government and organizations like us established negotiations with these communities and that's how we came up with the establishment of the Monarch Conservation Fund.

ZIYA TONG: In 2000, the monarch habitat was established as a nature reserve called the Monarch Butterfly BioSphere Reserve. And WWF worked with the Mexican government to make a deal with the loggers of Michoacán. If they stopped cutting down trees in the butterfly habitat, they could get access to employment opportunities and a fund that would provide them with the same amount of money they would have gotten from logging. And it totally worked. Between 2004 and 2008, illegal logging affected 2000 hectares in the reserve's core. In 2025, that number is way down—to just 2.5 hectares.

JORGE RICKARDS: We are also seeing some regeneration and restoration of forests. We have been working very, very hard. with the communities in doing restoration and reforestation of forests within the reserve with good results.

ZIYA TONG: But even with all of these efforts on the southern end of the monarch migration, their population is still dropping. That’s because of a lack of milkweed and other native plants. If a monarch can’t find milkweed to lay her eggs on, she’ll just keep looking and looking and looking until she dies. According to botanist Ryan Godfrey, it’s a problem that has an impact way beyond just monarch butterflies.

RYAN GODFREY: In Canada, and across North America, and around the world, studies on pollinator populations, insect populations, show that they're decreasing.

ZIYA TONG: Monarchs, and all butterflies, are pollinators, or creatures that help move pollen from one plant to another—but they aren’t very good at it.

RYAN GODFREY: So a butterfly, actually all butterflies, are considered to be what's called an incidental pollinator. So they might accidentally move some pollen that kind of sticks to their toes when they go from one place to another. If they were the only pollinators, there would not be a lot of plants that would get pollinated.

ZIYA TONG: With fewer nectar-producing plants, there are fewer butterflies. But it also means fewer bees, wasps, moths, and flies. And when all of those pollinator groups start disappearing, the ripple effect is massive.

RYAN GODFREY: If pollinators disappear, then it's a catastrophe. So for our crops in particular, it means that we will have to literally hand pollinate all of those plants. It would be extremely labor intensive and costly. And what it would mean is that many of the foods that we love to eat would either become unavailable or so expensive that most people can't afford to buy them.

ZIYA TONG: As of 2020, there are more than 70 species of pollinators currently listed as endangered or threatened, including many species of moths and bees. In countries with high pesticide use, economic losses from pollinator decline can be as high as $135 billion. That’s not just a problem for humans. It impacts every other creature on earth.

RYAN GODFREY: Most insects are food sources. They're literally the intermediaries between plants, which are the only creatures on Earth that can transform sunlight into sugar, and then insects take that sugar and turn it into their bodies, and then other creatures like mammals and birds can eat the insects. So that flow of energy would be completely disrupted. If insects disappeared, it would be devastating and would change the entire food web in a way that is hard to imagine, honestly. But any organism, any species that is involved in a food web that has insects in it, which is pretty much every species, would be impacted and the impact would be negative.

ZIYA TONG: So how can we stop that from happening? For Ryan, it starts with people remembering that this planet isn’t here just for us.

RYAN GODFREY: I would love to see more farmers seeing their land, the land where they grow plants, as an important part of an ecosystem. And so their practices have impact beyond just the food that they produce which is so important and we love them for doing that. They're also stewarding habitats for lots of different creatures.

ZIYA TONG: There are actually lots of ways for farms to build environments that are safe for monarchs and other insects. That might include turning space that isn’t usable for crops into a garden of native wildflowers, maintaining nearby forests, and thinking carefully about what kinds of herbicides get sprayed on crops. And individuals like you and me can help our insect neighbours out, too, by providing them with a safe place to land.

RYAN GODFREY: I grow native plants on my balcony. I grow them in my community garden. I grow them in my condo courtyard area and raised beds all through the city. I try to get them in every spot I can and everywhere that I put them I see butterflies and bees and other insects and then birds and everything showing up to be part of that ecosystem. So that is something that every one of us can do, wherever you are, I promise you there's a spot for native plants in your life.

ZIYA TONG: When it comes down to it, monarch butterflies may not be the most important creature in our ecosystem. They aren’t very good pollinators, and they also aren’t a very good source of food. But everywhere in the world, people love them.

JORGE RICKARDS: They somehow take us back to our childhood, no? They're so beautiful. They are harmless. They're colourful. And I guess that every one of us, when we were a child, we saw a butterfly, or maybe even held one and got fascinated by it.

RYAN GODFREY: I think monarchs are a flag bearer in a way. We see them, we recognize them, we care about them, and they're obvious. And their decline is also obvious. I've heard people say, tell me that, oh, there used to be a lot more monarchs. Why aren't there as many monarchs now as there used to be?

ZIYA TONG: That has its own kind of power—the power to draw people’s attention, to make us care, and to help us see our place in the greater web of nature.

RYAN GODFREY: That feeling of like there's the human world and the natural world and they're separated. That mindset which really pervades all of our systems, all of our industrial systems, our agricultural systems, our whole economic system is based on that premise and that's a huge barrier. So we need to tear down that wall and realize that there's not the human world and the natural world. There's just one world. We're all part of that world and everything we do is interconnected.

ZIYA TONG: Monarchs and other insects teach us how even the smallest creatures can help shape the world around us. They can take on journeys of thousands of kilometres and help fuel the food supply for billions of people. And without them, the world would be a little less beautiful. The good news is that every wildflower planted, every milkweed grown, every inch of forest protected, can help tip the scales—because even the smallest actions, like the flaps of the smallest wings, can carry the greatest power.

ZIYA TONG: Thanks for joining us today on This Is Wild! I’m your host, Ziya Tong. To learn more about the butterflies of Michoacan and more of WWF-Canada’s conservation work, you can check out wwf.ca/thisiswild. If you enjoyed this episode, please leave us a review on your favourite podcast app, and don’t forget to share this show with your friends! And if you have any questions or suggestions for the show, you can send us an email at thisiswild@wwfcanada.org. This Is Wild is created by WWF-Canada and Antica Productions. Our executive producers are Geoff Siskind, Laura Regehr, and Stuart Coxe. This episode was written and produced by Emily Morantz. Our production team at WWF-Canada is Joshua Ostroff, Erin Saunders, and Tina Knezevic. Nicole MacAdam is WWF's VP of Comms. Mixing and sound design by Philip Wilson.

Ziya Tong

Ziya Tong is an award-winning science journalist, known for making complex ideas accessible and engaging. She hosted Discovery Channel’s flagship show Daily Planet and has appeared on PBS, CBC and CTV. A passionate advocate for the planet, Ziya serves on the board of WWF-International, is the author of The Reality Bubble, about environmental blind spots, and co-director of the documentary Plastic People: The Hidden Crisis of Microplastics.